|

Size: 8641

Comment:

|

← Revision 2479 as of 2011-12-13 16:48:09 ⇥

Size: 9793

Comment:

|

| Deletions are marked like this. | Additions are marked like this. |

| Line 1: | Line 1: |

| == Down Under and Backwards == Many of you have had experiences traveling or moving to another country. The opportunity to immerse yourself into another culture can be quite exciting while also be a bit intimidating. Having recently moved to Australia from the US, I’ve been encountering many cultural differences that I have been forced to quickly adapt to. Not all have been so easy to grasp. Here’s just a few: |

## page was renamed from Labels & Indicators [[http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1449394639/ref=as_li_tf_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=4ourthmobile-20&linkCode=as2&camp=217145&creative=399373&creativeASIN=1449394639|{{attachment:wiki-banner-book.png|Click here to buy from Amazon.|align="right"}}]] == Down Under and Backward == Many of you have had experiences traveling or moving to another country. The oppor- tunity to become immersed into another culture can be quite exciting while also a bit intimidating. Having recently moved to Australia from the United States, I’ve been encountering many cultural differences that I have been forced to quickly adapt to. Not all have been so easy to grasp. Here are just a few. |

| Line 4: | Line 6: |

| === Phone numbers === The Australian Communications and Media Authority, who maintains and administers the telephone numbering plan, established a Full National Number (FNN) that is made up of 10 numbers - 0x xxxx-xxxx. The first two digits are the area code, the next four generally make up the Call Collection Area and Exchange. The last four numbers define the line number at the exchange. |

=== Phone Numbers === The Australian Communications and Media Authority, which maintains and administers the telephone numbering plan, established a Full National Number (FNN) that is composed of 10 numbers: 0x xxxx-xxxx. The first two digits are the area code; the next four generally make up the Call Collection Area and Exchange. The last four numbers define the line number at the exchange. |

| Line 7: | Line 9: |

| Mobile numbers also have 10 digits but follow a different structure. 04yy yxx-xxx. Originally, the y digits indicated the network carrier. But now that Australia allows for Wireless Number Portability (WLNP), like the US, there is not a fixed relationship between these numbers and the mobile carrier. | Mobile numbers also have 10 digits but follow a different structure: 04yy yxx-xxx. Originally, the y digits indicated the network carrier. But now that Australia allows for Wireless Number Portability (WLNP), like the United States, there is not a fixed relation- ship between these numbers and the mobile carrier. |

| Line 9: | Line 11: |

| So giving my new mobile number out to people was bit confusing. I was always following the landline format xx xxxx-xxxx and getting a few confused looks. | So, giving my new mobile number out to people was a bit confusing. I was always following the landline format of 0x xxxx-xxxx and getting a few confused looks. |

| Line 12: | Line 14: |

| So much to choose from, and so little knowledge! There’s E85, ULP (Unleaded) E10 (ULP + 10% ethanol), PULP (Premium), UPULP (Ultra Premium), Diesel, and LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas). Unlike the States, who sells per gallon, Australia sells it by the liter and is priced in cents. A typical petrol price of ULP may be 135.9. Having a US pricing format embedded in my head, I was shocked at first to think that gasoline was $135 per liter, though my sense quickly rationalize this was a wrong deduction. | So much to choose from, and so little knowledge! There’s E85, ULP (Unleaded), E10 (ULP + 10% ethanol), PULP (Premium), UPULP (Ultra Premium), Diesel, and LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas). Unlike the United States, where gas is sold by the gallon, Australia sells it by the liter and it is priced in cents. A typical petrol price of ULP may be 135.9. Having a US pricing format embedded in my head, I was shocked at first to think that gasoline was $135 per liter, though my sense quickly rationalized this was a wrong deduction. |

| Line 15: | Line 17: |

| My first experience to this confusion occurred when I was applying for both my Visa and overseas health insurance and had to enter my date of birth. The visa application was clear in the format I had to enter: day/month/year. The insurance form was not. It was a paper form with blank squares for each separate character: | My first experience with this confusion occurred when I was applying for both my Visa and my overseas health insurance and I had to enter my date of birth. The Visa application was clear in the format I had to enter: day/month/year. The insurance form was not. It was a paper form with blank squares for each separate character. |

| Line 17: | Line 19: |

| The empty boxes had no label under them. Just: ☐☐-☐☐-☐☐☐. | The empty boxes had no label under them, just: ☐ ☐ - ☐ ☐ - ☐ ☐ ☐. |

| Line 19: | Line 21: |

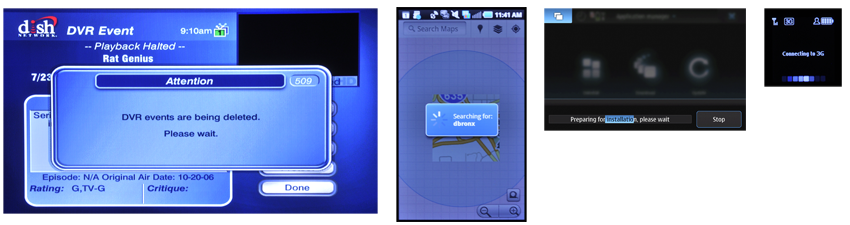

| In Australia, this format is a culturally understood. However, for me, it’s quite unclear. Do I enter my month or day first? Each of those fit within the constraints of provided format. Yet each clearly yields an entirely different result. == Understanding our users == As designers, we can limit these confusions by designing better UIs that meet the needs of our users. To do this, we must consider who are users are, what type of prior knowledge they have, as well as the context in which the device will be used. === Users and their prior knowledge === Mobile users come from a variety of cultures with a multitude of experiences, skills, and expectations. If the devices’ UI cannot meet these user requirements, their experiences will quickly turn into frustrations while their actions result in performance errors. To prevent this, start by identifying your users early in the design process. Use methods of observation, interviews, personas and storyboards to gain insight into their needs, motivations and experiences. Refer to this collected rich data to validate and guide your design decisions throughout the design process. === Context of use === Unlike desktop, mobile users will use the device anywhere and anytime. These users may be checking an email while walking down the street, snapping photos during a design GUI jam, or lying in bed playing a game. In all of these situations, external stimuli are present which affect the user’s amount of attention he can use to focus on the task at hand: lighting conditions, external noise, body movements are all stimuli that affect one’s attention. Consider the effects of how bright sunlight on a glossy screen limits our ability to distinguish details, colors and character legibility. Or when the device is shaking up and down in the hands of the user as they walk down the street, selecting and element on the screen becomes prone to error. These external stimuli are not always controllable, but the device’s UI can at least be designed to limit their negative affects on the user experience. Using labels and indicators can redirect the user’s attention away from the external stimuli back to task at hand. == Labels & Indicators in the mobile space == * Label: Either text or image that provides clear and accurate information to support an element’s function. * Indicator: A graphical element supported by text to provide cues, and/or user control on the status or changes. As you are now aware, displayed information is not always easily understood or easily detectable. The use of labels and indicator widgets can provide assistance to these issues through surface level visual cues and functions. These visual cues and functions can help our users better understand the current context within the device. Labels and indicators can be used on the mobile space to: * Indicate the current status or progress of the state of the device. * Present additional information, tips, or advice to clarify the current context. * Present information, especially text and numerical data, in the most appropriate and recognizable format for the context and viewer. * Provide user controls for operations involving access to remote servers. === Visual Guidelines for labels and indicators on the mobile space === {{attachment:LabelsIntro-Wait.png|As we get better and better hardware and networks, we ask more of them. Delays appear to be inevitable. Do what you can to indicate in context, so the user has some information to occupy them.|align=right}} * When using small text to label, there must be a luminance color contrast from the background. The ISO recommends at least a 3:1 ratio between the luminance of text to the luminance of background color. * When using color to show detail, luminance contrast is the most important principle. Using black and white together have the strongest contrast. Other effective combinations are yellow on black and dark blue on white (Ware, 2008). * Use symbols that are easily understood and represent the intended function. Use symbols familiar to your users, not to the designers and developers. * When using animation, objects that have a constant motion may become habituated to the user, and may end up being ignored. * If an object must grab a user’s attention, consider having it emerge, disappear, and reemerge every few seconds or couple of minutes into the visual field. Be mindful of the overuse of multiple objects moving on a screen. The user will become easily distracted. * Objects used to signal the user, should emerge and disappear every few seconds or minutes to reduce habituation. * Use motion, such as rotation or fill, to indicate an ongoing status change. Static objects provide a lack of feedback when it comes to progress or status. Users might feel such an indicator has “frozen up” if it lacks motion, especially if it has arrows or otherwise evokes movement. * When possible, use images that evoke meaning, emotion, or desire to your users. These images will increase the user’s motivation to attend to these objects. If objects lack these emotional values, users will overlook and avoid them. One example is to use recognizable images as avatars that represent people we know. This works effectively well in contact lists. Be user to avoid “default” objects that are repeated. |

In Australia, this format is culturally understood. However, for me it’s quite unclear. Do I enter my month or day first? Each of those fits within the constraints of the provided format. Yet each clearly yields an entirely different result. |

| Line 60: | Line 24: |

| == Patterns for Labels & Indicators == Using appropriate and consistent Label & Indicator widgets provide visual cues and functions to communicate the current context of the device. Within this chapter, the following patterns will be discussed, based on how the human mind organizes and navigates information: |

== Understanding Our Users == As designers, we can limit these confusions by designing better UIs that meet the needs of our users. To do this, we must consider who are users are, what type of prior knowledge they have, and the context in which the device will be used. === Users and Their Prior Knowledge === Mobile users come from a variety of cultures with a multitude of experiences, skills, and expectations. If the devices’ UI cannot meet these user requirements, their experiences will quickly turn into frustrations while their actions result in performance errors. To prevent this, start by identifying your users early in the design process. Use methods of observation, interviews, personas, and storyboards to gain insight into their needs, motivations, and experiences. Refer to this collected data to validate and guide your design decisions throughout the design process. === Context of Use === Unlike desktop users, mobile users will use their devices anywhere and anytime. These users may be checking an email while walking down the street, snapping photos during a design GUI jam, or lying in bed playing a game. In all of these situations, external stimuli are present which affect the amount of attention the user can use to focus on the task at hand: lighting conditions, external noise, and body movements are all stimuli that affect one’s attention. Consider the effects of how bright sunlight on a glossy screen limits our ability to distinguish details, colors, and character legibility. Similarly, when the device is shaking up and down in the hands of the user as he walks down the street, selecting an element on the screen becomes prone to error. These external stimuli are not always controllable, but the device’s UI can at least be designed to limit the negative effects on the user experience. Using labels and indicators can redirect the user’s attention away from the external stimuli and back to the task at hand. == Labels and Indicators in the Mobile Space == ''Labels'' are either text or images that provide clear and accurate information to support an element’s function. ''Indicators'' are graphical elements supported by text to provide cues and/or user control on the status or changes. As you are now aware, displayed information is not always easily understood or easily detectable. The use of labels and indicator widgets can provide assistance with these issues through surface-level visual cues and functions. These visual cues and functions can help our users better understand the current context within the device. Labels and indicators can be used in the mobile space to: * Indicate the current status or progress of the state of the device (Figure 7-1) * Present additional information, tips, or advice to clarify the current context * Present information, especially text and numerical data, in the most appropriate and recognizable format for the context and viewer * Provide user controls for operations involving access to remote servers === Visual Guidelines for Labels and Indicators in the Mobile Space === [[http://www.flickr.com/photos/shoobe01/6501531885/|{{attachment:LabelsIntro-Wait.png|Figure 7-1. As we get better and better hardware and networks, we ask more of them. Delays appear to be inevitable. Do what you can to label, and communicate within context, so that users have some information to occupy and guide them.}}]] The following are some visual guidelines for using labels and indicators on mobile devices: * When using small text for a label, there must be a luminance color contrast from the background. The ISO recommends at least a 3:1 ratio between the luminance of text to the luminance of background color. * When using color to show detail, luminance contrast is the most important principle. Using black and white together has the strongest contrast. Other effective combinations are yellow on black and dark blue on white (Ware 2008). * Use symbols that are easily understood and represent the intended function. Use symbols familiar to your users, not to the designers and developers. * When using animation, objects that have a constant motion may become habituated to the user, and may end up being ignored. * If an object must grab a user’s attention, consider having it emerge, disappear, and re- emerge every few seconds or minutes into the visual field. Be mindful of the overuse of multiple objects moving on a screen. The user will become easily distracted. * Objects used to signal the user should emerge and disappear every few seconds or minutes to reduce habituation. * Use motion, such as rotation or fill, to indicate an ongoing status change. Static ob- jects provide a lack of feedback when it comes to progress or status. Users might feel such an indicator has “frozen up” if it lacks motion, especially if it has arrows or otherwise evokes movement. * When possible, use images that evoke meaning, emotion, or desire to your users. These images will increase the user’s motivation to attend to these objects. If objects lack these emotional values, users will overlook and avoid them. One example is to use recognizable images as avatars that represent people we know. This works effectively well in contact lists. Better to avoid “default” objects that are repeated (Saffer 2005). == Patterns for Labels and Indicators == Using appropriate and consistent label and indicator widgets provides visual cues and functions to communicate the current context of the device. In this chapter, we will discuss the following patterns based on how the human mind organizes and navigates information: ''[[Ordered Data]]'' Presents textual information in the most appropriate and recognizable format for the context and viewer, while considering user expectations, norms, and display size constraints ''[[Tooltip]]'' A small label, descriptor, or additional piece of information that is displayed to fur- ther explain a piece of content, a component, or a control ''[[Avatar]]'' An iconic image or profile used to represent or support the label for an individual ''[[Wait Indicator]]'' An indicator used to inform the delay status of a loading component ''[[Reload, Synch, Stop]]'' User controls for operations involving access to remote servers, including override |

| Line 64: | Line 78: |

| * [[Ordered Data]] Presents textual information in the most appropriate and recognizable format for the context and viewer while considering user expectations, norms, and display size constraints. * [[Tooltip]] A small label, descriptor or additional piece of information is displayed to further explain a piece of content, a component or a control. * [[Avatar]] An iconic image or profile used to represent or support the label for an individual. * [[Wait Indicator]] An indicator used to inform the delay status of a loading component. * [[Reload, Synch, Stop]] User controls for operations involving access to remote servers including override. |

------- = Discuss & Add = Please do not change content above this line, as it's a perfect match with the printed book. Everything else you want to add goes down here. == Examples == If you want to add examples (and we occasionally do also) add them here. == Make a new section == Just like this. If, for example, you want to argue about the differences between, say, Tidwell's Vertical Stack, and our general concept of the List, then add a section to discuss. If we're successful, we'll get to make a new edition and will take all these discussions into account. |

Down Under and Backward

Many of you have had experiences traveling or moving to another country. The oppor- tunity to become immersed into another culture can be quite exciting while also a bit intimidating. Having recently moved to Australia from the United States, I’ve been encountering many cultural differences that I have been forced to quickly adapt to. Not all have been so easy to grasp. Here are just a few.

Phone Numbers

The Australian Communications and Media Authority, which maintains and administers the telephone numbering plan, established a Full National Number (FNN) that is composed of 10 numbers: 0x xxxx-xxxx. The first two digits are the area code; the next four generally make up the Call Collection Area and Exchange. The last four numbers define the line number at the exchange.

Mobile numbers also have 10 digits but follow a different structure: 04yy yxx-xxx. Originally, the y digits indicated the network carrier. But now that Australia allows for Wireless Number Portability (WLNP), like the United States, there is not a fixed relation- ship between these numbers and the mobile carrier.

So, giving my new mobile number out to people was a bit confusing. I was always following the landline format of 0x xxxx-xxxx and getting a few confused looks.

Gas Types and Pricing

So much to choose from, and so little knowledge! There’s E85, ULP (Unleaded), E10 (ULP + 10% ethanol), PULP (Premium), UPULP (Ultra Premium), Diesel, and LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas). Unlike the United States, where gas is sold by the gallon, Australia sells it by the liter and it is priced in cents. A typical petrol price of ULP may be 135.9. Having a US pricing format embedded in my head, I was shocked at first to think that gasoline was $135 per liter, though my sense quickly rationalized this was a wrong deduction.

Date Format

My first experience with this confusion occurred when I was applying for both my Visa and my overseas health insurance and I had to enter my date of birth. The Visa application was clear in the format I had to enter: day/month/year. The insurance form was not. It was a paper form with blank squares for each separate character.

The empty boxes had no label under them, just: ☐ ☐ - ☐ ☐ - ☐ ☐ ☐.

In Australia, this format is culturally understood. However, for me it’s quite unclear. Do I enter my month or day first? Each of those fits within the constraints of the provided format. Yet each clearly yields an entirely different result.

Understanding Our Users

As designers, we can limit these confusions by designing better UIs that meet the needs of our users. To do this, we must consider who are users are, what type of prior knowledge they have, and the context in which the device will be used.

Users and Their Prior Knowledge

Mobile users come from a variety of cultures with a multitude of experiences, skills, and expectations. If the devices’ UI cannot meet these user requirements, their experiences will quickly turn into frustrations while their actions result in performance errors.

To prevent this, start by identifying your users early in the design process. Use methods of observation, interviews, personas, and storyboards to gain insight into their needs, motivations, and experiences. Refer to this collected data to validate and guide your design decisions throughout the design process.

Context of Use

Unlike desktop users, mobile users will use their devices anywhere and anytime. These users may be checking an email while walking down the street, snapping photos during a design GUI jam, or lying in bed playing a game.

In all of these situations, external stimuli are present which affect the amount of attention the user can use to focus on the task at hand: lighting conditions, external noise, and body movements are all stimuli that affect one’s attention. Consider the effects of how bright sunlight on a glossy screen limits our ability to distinguish details, colors, and character legibility. Similarly, when the device is shaking up and down in the hands of the user as he walks down the street, selecting an element on the screen becomes prone to error.

These external stimuli are not always controllable, but the device’s UI can at least be designed to limit the negative effects on the user experience. Using labels and indicators can redirect the user’s attention away from the external stimuli and back to the task at hand.

Labels and Indicators in the Mobile Space

Labels are either text or images that provide clear and accurate information to support an element’s function.

Indicators are graphical elements supported by text to provide cues and/or user control on the status or changes.

As you are now aware, displayed information is not always easily understood or easily detectable. The use of labels and indicator widgets can provide assistance with these issues through surface-level visual cues and functions. These visual cues and functions can help our users better understand the current context within the device. Labels and indicators can be used in the mobile space to:

- Indicate the current status or progress of the state of the device (Figure 7-1)

- Present additional information, tips, or advice to clarify the current context

- Present information, especially text and numerical data, in the most appropriate and recognizable format for the context and viewer

- Provide user controls for operations involving access to remote servers

Visual Guidelines for Labels and Indicators in the Mobile Space

The following are some visual guidelines for using labels and indicators on mobile devices:

- When using small text for a label, there must be a luminance color contrast from the background. The ISO recommends at least a 3:1 ratio between the luminance of text to the luminance of background color.

- When using color to show detail, luminance contrast is the most important principle. Using black and white together has the strongest contrast. Other effective combinations are yellow on black and dark blue on white (Ware 2008).

- Use symbols that are easily understood and represent the intended function. Use symbols familiar to your users, not to the designers and developers.

- When using animation, objects that have a constant motion may become habituated to the user, and may end up being ignored.

- If an object must grab a user’s attention, consider having it emerge, disappear, and re- emerge every few seconds or minutes into the visual field. Be mindful of the overuse of multiple objects moving on a screen. The user will become easily distracted.

- Objects used to signal the user should emerge and disappear every few seconds or minutes to reduce habituation.

- Use motion, such as rotation or fill, to indicate an ongoing status change. Static ob- jects provide a lack of feedback when it comes to progress or status. Users might feel such an indicator has “frozen up” if it lacks motion, especially if it has arrows or otherwise evokes movement.

- When possible, use images that evoke meaning, emotion, or desire to your users. These images will increase the user’s motivation to attend to these objects. If objects lack these emotional values, users will overlook and avoid them. One example is to use recognizable images as avatars that represent people we know. This works effectively well in contact lists. Better to avoid “default” objects that are repeated (Saffer 2005).

Patterns for Labels and Indicators

Using appropriate and consistent label and indicator widgets provides visual cues and functions to communicate the current context of the device. In this chapter, we will discuss the following patterns based on how the human mind organizes and navigates information: Ordered Data

- Presents textual information in the most appropriate and recognizable format for the context and viewer, while considering user expectations, norms, and display size constraints

- A small label, descriptor, or additional piece of information that is displayed to fur- ther explain a piece of content, a component, or a control

- An iconic image or profile used to represent or support the label for an individual

- An indicator used to inform the delay status of a loading component

- User controls for operations involving access to remote servers, including override

Discuss & Add

Please do not change content above this line, as it's a perfect match with the printed book. Everything else you want to add goes down here.

Examples

If you want to add examples (and we occasionally do also) add them here.

Make a new section

Just like this. If, for example, you want to argue about the differences between, say, Tidwell's Vertical Stack, and our general concept of the List, then add a section to discuss. If we're successful, we'll get to make a new edition and will take all these discussions into account.