The page is the area that you will spend your time designing for any application or website. A part of it is visible in the viewport of the mobile screen during its current state. There are states and modes and versions to be considered, as well as addressing what is fixed to the page, what can float, and what is locked to the viewport.

The page is the area that you will spend your time designing for any application or website. A part of it is visible in the viewport of the mobile screen during its current state. There are states and modes and versions to be considered, as well as addressing what is fixed to the page, what can float, and what is locked to the viewport.

Based on cultural norms of reading conventions and how people process information, you have to design elements for the page, and place items on it in ways your users will understand. You also want to create information that is easy to access and easy to locate. Your users are not stationary, nor are they focused entirely on the screen. They’re everywhere, and they want information quickly and to be able to manipulate it easily.

Unlike later parts of this book, which cover broader topics, the Page patterns that we will discuss here are contained in only a single chapter:

Chapter 1, Composition

Helpful Knowledge for This Section

Before you dive into the patterns, we will provide you with some extra knowledge in the section introductions. This extra knowledge is in multidisciplinary areas of human factors, engineering, psychology, art, or whatever else we feel is relevant.

For this particular section, we will provide background knowledge for you in the following areas:

- Digital display page layout guidelines

- Page layout guidelines for mobile users

Digital Display Page Layout Principles

The composition of a page has to do with the assembly of components, concepts, content, and other elements to build up the final design. As we already know, consistency is important, so these elements are not placed arbitrarily on the page, or even just as the one page dictates, but on rules across the system, or even the whole OS.

At the highest level is the grid. This is a regularized series of guides, defining the spacing and alignment of the main elements on all the pages in the system, as shown in Figure I-1. Some rules are inviolable, such as margins, and some are specifically designed to offer options for special page layouts, or unexpected future changes.

From these are developed a series of templates, from which each page in the application, site, or other process will be designed and built. This encourages a consistent user and brand experience that supports content organization and layout, advertising require- ments, navigation, and message display characteristics such as legibility and readability.

Patterns within Chapter 1, such as Fixed Menu, Revealable Menu, Notifications, and Titles, are repeated at the same place on each and every page, and so reside in each template. A subsidiary concept is that of the wrapper, which defines these common compo- nents—and others, such as scroll bars—so that they are consistently designed and built for each and every page template.

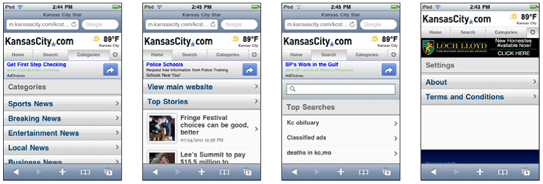

Mobile users have specific tasks and goals. They require that the information be quickly located and effectively organized. Therefore, the page layouts need to reflect the mental models and schemas understood by users. If you ignore these, you will end up with situations such as that shown in Figure I-2. Your users can become frustrated and dissatisfied with their experience, create miscues and errors, and maybe even give up!

Furthermore, using page layouts wisely allows you to organize and place content effec- tively on valuable screen real estate, where every pixel is important.

Page Layout Guidelines for Mobile Users

Here are some page layout guidelines to follow:

- Mobile screen real estate is valuable. Avoid the use of banners, bars, images, and graphics that take up space without any specific use. This use may be secondary, such as communicating the hierarchy or structure, but the designer should always be able to describe the reason.

- Lay out elements within a design hierarchy. There are optional versions, and some interactive types insist that time is another component, but for simplicity the hierarchy is Position → Size → Shape → Contrast → Color → Form. The most important items are larger, higher, brighter, and so on.

Consider the Gestalt laws of Closure, Continuity, Figure and Ground, Proximity, Relative Size, Similarity, and Symmetry. These are discussed further in Part II, Components.

- Use consistent and simple navigation elements. People have limits to the amount of information they can store in their short-term memory. Therefore, they automatically filter information that is important and stands out. Information elements that are excessively displayed and irrelevant will be ignored and overlooked.

- Wayfinding is really rooted in real-world navigation, like getting around town or finding the right room in a building. Kevin Lynch, an environmental psychologist, established five wayfinding elements that people use to identify their position: Paths, Edges, Nodes, Landmarks, and Districts. These same environmental elements are also referenced when navigating digital content on websites or mobile devices. Page numbers, titles, headers and footers, tabs, links, and more provide a lot of help that we’ve inherited almost as a whole for interactive design.

Consider how users will view your page when plotting content. Generally, users will look for high-priority information in the upper left of the content area (Nielsen 2010).

- Multicolumn text is not used to meet some design style, but to restrict line length. And line lengths are not based on fixed sizes, or even percentages of page width, but on character count. Long lines are harder to read. Around 60 to 65 characters (on average) is the maximum length you want to use. A definition for what is too short depends on how many long words you have.

- Titles describe pages, elements within a page, and content sections. Use them consistently and appropriately.

- Default text alignment is left. For right-to-left UI languages, default text alignment is right.

- Try to use bulleted information instead of a table.

The term false bottom, or false top, is specific to interactive design and refers to users thinking they are at the end of the content and not continuing to scroll. If text flows from one column to the next or one page to the next, it must be designed so that the relationship between the columns or pages is clear. “Continued on page 86” is all but a hyperlink from the past, which has been inherited by interactive; “Read the rest of this blog post” is basically the same thing.

Interactive systems have an additional challenge in that the page might be larger than the screen (or viewport, as we often call it).

Getting Started

You now have a general understanding that a page is an area that occupies the viewport of a mobile display. Pages can use a wrapper template to organize information consistently across the OS that will allow for a satisfying user experience. When making design decisions you must consider everything in this page section, even if you don’t have control (i.e., you’re not building an OS). You must know what it might do to your design. Consider your user’s goals and cognitive abilities, page layout guidelines, and the impor- tance of legibility and readability in message displays.

The following chapter will provide specific information on theory and tactics, and will illustrate examples of appropriate design patterns. Always remember to read the antipatterns, to make sure you don’t misuse or overuse a pattern.

Next: Composition

Discuss & Add

Please do not change content above this line, as it's a perfect match with the printed book. Everything else you want to add goes down here.

Examples

If you want to add examples (and we occasionally do also) add them here.

Make a new section

Just like this. If, for example, you want to argue about the differences between, say, Tidwell's Vertical Stack, and our general concept of the List, then add a section to discuss. If we're successful, we'll get to make a new edition and will take all these discussions into account.