|

Size: 11878

Comment:

|

← Revision 149 as of 2013-04-10 23:51:06 ⇥

Size: 10423

Comment:

|

| Deletions are marked like this. | Additions are marked like this. |

| Line 1: | Line 1: |

| A Page is the area that occupies the entire viewport of the screen during its current state. It organizes information while considering: * Display technology. * Navigation structures and interactions. * Message display characteristics. |

{{{#!html |

| Line 6: | Line 3: |

| == Message Display Characteristics == == Legibility == Refers to the ease with which the elements (letters, numbers, symbols, etc.) can be detected and discriminated from one another. === Font design === '''Font vs. Typeface''' |

<div class="saleshead"> <div class="block" id="left"> <a href="http://4ourth.com/wiki/4ourth%20Mobile%20Touch%20Template"> <div class="salesLeft"> <h3>4ourth Mobile Touch Template</h3> <p>Design for people, not pixels with this handy, wallet-sized inspection and design tool, only $10. <span>Order yours now</span></p> </div> </a> </div> <div class="block" id="right"> <a href="http://4ourth.com/wiki/Mobile%20Design%20Patterns%20Poster"> <div class="salesRight"> <h3>Mobile Interaction Design Patterns Poster</h3> <p>Every pattern from the book and this wiki, plus easy-to-follow relationships, and key information on sizes for readability and touch. <span>Order now</span></p> </div> </a> </div> <div class="salespad"> </div> </div> |

| Line 12: | Line 24: |

| Typeface is a collection of characters-letters, numbers, symbols, punctuation marks, etc. In contrast, a font is a physical thing, the description of the typeface-in computer code, photographic film, or metal-used to image the type (Felici: 2003). When choosing the appropriate display font, we must understand the difference between anti-aliased and bitmapped letters because these affect legibility. |

}}} |

| Line 15: | Line 26: |

| Ant-aliasing renders some of pixels shades of gray along the edges of the letter. This helps users to perceive the letter as being smooth. Anti-aliased text is more legible when using larger font sizes for Titles and headings; however, using anti-aliasing text in small font sizes tends to create a blurry image. | [[http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1449394639/ref=as_li_tf_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=4ourthmobile-20&linkCode=as2&camp=217145&creative=399373&creativeASIN=1449394639|{{attachment:wiki-banner-book.png|Click here to buy from Amazon.|align="right"}}]]The ''page'' is the area that you will spend your time designing for any application or website. A part of it is visible in the viewport of the mobile screen during its current state. There are states and modes and versions to be considered, as well as addressing what is fixed to the page, what can float, and what is locked to the viewport. |

| Line 17: | Line 28: |

| === Baselines and Measurements === * '''Baseline'''- is the axis where the main body of text sits. Some letters may slightly extend below the baseline * '''X-height'''- is the height of the main lowercase body from the baseline. It is the size of the lower case letter x. It excludes ascenders and descenders. For Mobile and Small-Screen Devices, the x-height must be between 65 and 80% of the cap height. * '''Cap height'''- is the distance from the baseline to the height of the capital letter and the ascender. When figuring a font’s point size, the cap height is used. * '''Descender Line'''-The descender is the part of a letter that extends below the baseline. The descender line is the axis in which all descenders within the font family rest against. For Mobile and Small-Screen Devices, do not use excessive descenders – avoid exceeding 15 - 20% of the cap-height, to avoid excessive leading. * '''Ascender'''- An ascender is part of the letter that extends above the x-height. For Mobile and Small-Screen Devices, do not have ascenders above the cap height – critical for non-English languages === Letterforms and their parts === * '''Serifs''' - are finishing flourishes at the ends of a character’s main stroke. They extend outward. They are not solely decorative. They also help with our ability to discriminate other characters that make up lines of text. Serif faces are more readable for large blocks of type than sans serif faces. If your application is one filled with news articles, or something similar, consider if a serif face might work. * '''San-Serifs''' - For mobile type, sans-serif is often the default choice as it works well enough for all uses, at all sizes. * '''Square Serifs''' - Square serifs may be a good compromise, to assure the serifs display at the rendered sizes. === Letter height === Measure, Point Size, and Leading |

Based on cultural norms of reading conventions and how people process information, you have to design elements for the page, and place items on it in ways your users will understand. You also want to create information that is easy to access and easy to locate. Your users are not stationary, nor are they focused entirely on the screen. They’re everywhere, and they want information quickly and to be able to manipulate it easily. |

| Line 30: | Line 30: |

| Measure refers to the width of the column that type is set in. | Unlike later parts of this book, which cover broader topics, the Page patterns that we will discuss here are contained in only a single chapter: * '''Chapter 1, [[Composition]]''' |

| Line 32: | Line 33: |

| '''Letter Height:''' | |

| Line 34: | Line 34: |

| Points-One point equals 1/72 of an inch or .35 milimeters. | == Helpful Knowledge for This Section == Before you dive into the patterns, we will provide you with some extra knowledge in the section introductions. This extra knowledge is in multidisciplinary areas of human factors, engineering, psychology, art, or whatever else we feel is relevant. |

| Line 36: | Line 37: |

| Pica-12 points equal one pica. A pica is the unit usually used to measure the width of columns. | For this particular section, we will provide background knowledge for you in the following areas: * Digital display page layout guidelines * Page layout guidelines for mobile users |

| Line 38: | Line 41: |

| Em-During the letterpressing era, letters were created from cast sorts. In metal type, the height from the top to the bottom of the metal sort was known as its point size. In digital type, the Em | |

| Line 40: | Line 42: |

| Letter Width: Letter Width is known as set width. Set width measures the width of the letter and a small cushion. During the 18th century, standardizing the measuring of type began. When === Upper/lower case === === Stroke width/weight === === Letter/line spacing === === Contrast === Illumination/luminance: Brightness refers to our subjective perception of how bright an object is. |

== Digital Display Page Layout Principles == The [[Composition|composition]] of a page has to do with the assembly of components, concepts, content, and other elements to build up the final design. As we already know, consistency is important, so these elements are not placed arbitrarily on the page, or even just as the one page dictates, but on rules across the system, or even the whole OS. |

| Line 48: | Line 45: |

| Luminance is the measure of light an object gives emits from its surface. Luminance is measured in different units such as candela (cd/m^2), footlambert (ftL), mililambert (mL), and Nit (nt). Riggs (1971) notes that in starlight (luminance of .0003 cd/m^2) we can see the white pages of a book but not the writing on them. The recommended luminance standard for measuring acuity is 85 cd/m^2 (Olzak and Thomas, 1996). | [[http://www.flickr.com/photos/shoobe01/6502093057/|{{attachment:PageSectionIntro-Grid.png|Figure I-1. Developing a common grid and hierarchy of information for the entire application or site is key to a consistently usable and consistently branded experience. After a grid such as this is created and wrapper elements are defined, a series of templates can be created, and then individual pages and states.}}]] |

| Line 50: | Line 47: |

| Remember that Luminance and Brightness are unrelated. For example, if you lay out a piece of black paper in full sunlight on a bright day, you may measure a value of 1000 cd/m^2. If you view a white piece of paper in an office light , you will probably measure a value of only 50 cd/m^2. Thus, a black object on a bright day outside may reflect 20 times more light than white paper in the office (Ware, 2000). == Legibility Guidelines for Mobile Devices == * Avoid using all caps for text. Users read paragraphs in all caps about 10% slower than mixed cases. (Nielsen, 2000). * Try and use plain-color backgrounds with text because graphical or pattern backgrounds interfere with the eye’s ability to discriminate the difference. * Sans-serif is often the default choice as it works well enough for all uses, at all sizes. Consider using Helvetica (iPhone’s default typeface), Verdana is also good while it has a larger x-height and simpler curves than Helvetica. * Almost all text should be left justified. * Strong counters (or "counter-forms") – often, using squared-off shapes for small counters is a good idea * Use typefaces with un-stressed forms – straight, even-width lines. |

At the highest level is the ''grid''. This is a regularized series of guides, defining the spacing and alignment of the main elements on all the pages in the system, as shown in Figure I-1. Some rules are inviolable, such as margins, and some are specifically designed to offer options for special page layouts, or unexpected future changes. From these are developed a series of templates, from which each page in the application, site, or other process will be designed and built. This encourages a consistent user and brand experience that supports content organization and layout, advertising require- ments, navigation, and message display characteristics such as legibility and readability. Patterns within Chapter 1, such as [[Fixed Menu]], [[Revealable Menu]], [[Notifications]], and [[Titles]], are repeated at the same place on each and every page, and so reside in each template. A subsidiary concept is that of the ''wrapper'', which defines these common compo- nents—and others, such as scroll bars—so that they are consistently designed and built for each and every page template. Mobile users have specific tasks and goals. They require that the information be quickly located and effectively organized. Therefore, the page layouts need to reflect the mental models and schemas understood by users. If you ignore these, you will end up with situations such as that shown in Figure I-2. Your users can become frustrated and dissatisfied with their experience, create miscues and errors, and maybe even give up! Furthermore, using page layouts wisely allows you to organize and place content effec- tively on valuable screen real estate, where every pixel is important. == Page Layout Guidelines for Mobile Users == {{attachment:PageSectionIntro-KCcom.png|Figure I-2. If you don’t follow the principles of a grid and templates, you will end up applying components in overly variable ways. Here, the title is far below the tab, separated by the banner ad. On the search page, there is a search dialog above the title, pushing it farther down. On the home page, the addition of the “more” icon makes it unclear whether “Top Stories” is the page title, section title, or something else. And in Settings, the new style of banner draws the eye, so it seems, for a moment, that this is the title.}} Here are some page layout guidelines to follow: * Mobile screen real estate is valuable. Avoid the use of banners, bars, images, and graphics that take up space without any specific use. This use may be secondary, such as communicating the hierarchy or structure, but the designer should always be able to describe the reason. * Lay out elements within a design hierarchy. There are optional versions, and some interactive types insist that time is another component, but for simplicity the hierarchy is Position → Size → Shape → Contrast → Color → Form. The most important items are larger, higher, brighter, and so on. * Consider the Gestalt laws of Closure, Continuity, Figure and Ground, Proximity, Relative Size, Similarity, and Symmetry. These are discussed further in Part II, [[Components]]. * Use consistent and simple navigation elements. People have limits to the amount of information they can store in their short-term memory. Therefore, they automatically filter information that is important and stands out. Information elements that are excessively displayed and irrelevant will be ignored and overlooked. * Wayfinding is really rooted in real-world navigation, like getting around town or finding the right room in a building. Kevin Lynch, an environmental psychologist, established five wayfinding elements that people use to identify their position: Paths, Edges, Nodes, Landmarks, and Districts. These same environmental elements are also referenced when navigating digital content on websites or mobile devices. Page numbers, titles, headers and footers, tabs, links, and more provide a lot of help that we’ve inherited almost as a whole for interactive design. Consider how users will view your page when plotting content. Generally, users will look for high-priority information in the upper left of the content area (Nielsen 2010). * Multicolumn text is not used to meet some design style, but to restrict line length. And line lengths are not based on fixed sizes, or even percentages of page width, but on character count. Long lines are harder to read. Around 60 to 65 characters (on average) is the maximum length you want to use. A definition for what is too short depends on how many long words you have. * Titles describe pages, elements within a page, and content sections. Use them consistently and appropriately. * Default text alignment is left. For right-to-left UI languages, default text alignment is right. * Try to use bulleted information instead of a table. * The term ''false bottom'', or ''false top'', is specific to interactive design and refers to users thinking they are at the end of the content and not continuing to scroll. If text flows from one column to the next or one page to the next, it must be designed so that the relationship between the columns or pages is clear. “Continued on page 86” is all but a hyperlink from the past, which has been inherited by interactive; “Read the rest of this blog post” is basically the same thing. * Interactive systems have an additional challenge in that the page might be larger than the screen (or ''viewport'', as we often call it). |

| Line 61: | Line 78: |

| == Conspicuity == Conspicuity, while involving legibility, also implies other display characteristics. It is nicely summed up by the notion of signal/noise ratio–the ease with which a given piece of information is detectable in the presence of other competing information. === Spatial coding (grouping) === === Shape coding === === Color coding === Color can be used both to classify and emphasize information displayed on a screen. When using color for these things, you need to understand that we have limits in our processing abilities that affect our signal detection. |

== Getting Started == You now have a general understanding that a page is an area that occupies the viewport of a mobile display. Pages can use a wrapper template to organize information consistently across the OS that will allow for a satisfying user experience. When making design decisions you must consider everything in this page section, even if you don’t have control (i.e., you’re not building an OS). You must know what it might do to your design. Consider your user’s goals and cognitive abilities, page layout guidelines, and the impor- tance of legibility and readability in message displays. |

| Line 68: | Line 81: |

| In 18xx, A German psychologist Ewald Hering theorized that there are six elementary colors that are arranged perceptually as opponent pairs along three axes. These pairs are: black-white, red-green, and yellow-blue. Each color either is positive (excitatory) or negative (inhibitor). These opponent colors are never perceived at the same time because the visual system cannot be simultaneously excited and inhibited. | The following chapter will provide specific information on theory and tactics, and will illustrate examples of appropriate design patterns. Always remember to read the antipatterns, to make sure you don’t misuse or overuse a pattern. |

| Line 70: | Line 83: |

| Our modern color theory stems off of this. Today, we know that the input from the cones is processed intro three distinct channels: The luminance channel (black-white) is based on input from all of the cones. We have two chromatic channels. The red-green channel is based on the difference of long and middle-wavelength cone signals. The yellow-blue channel is based on the difference between the short-wavelength cons and the sum of the other two (Ware, 2000). | |

| Line 72: | Line 84: |

| In 1986, Post and Green created an experiment to test how subjects could effectively name 210 colors on a computer screen. The results of that test that are worth noting are: * The pure monitor red was actually named orange most of the time. * A true red color required the addition of a blue monitor primary. * Eight colors out of the 210 were consistently named, suggesting that only a small number of colors should be used to label categories. |

|

| Line 77: | Line 85: |

| Color for Labeling, or more technically – nominal information coding, is used to because color can be an effective way to make objects easy to remember and visually classify. Perceptual factors to be considered in choosing a set of color labels: 1. '''Distinctness''': 2. '''Unique hues''': Based on the Opponent Theory, they are: Red, Green, Yellow, Blue, Black, and White. 3. '''Contrast with background''': Our eyes are edge detectors. When we have objects that must be in front of a variety of backgrounds, it may be beneficial to have a thin white or black border around the color-coded object. Consider the reasons why alert street signs, have the border, too. 4. '''Color blindness''': About 7% of males and only 0.5% of females are color blind in some way. The most common is being red-green colorblind. 5. '''Number''': We are limited in the number of color-codes we can rapidly perceive. Studies recommend use between five and ten codes. 6. '''Field Size''': Object size affects how you should color code. Small color-coded objects less than half a degree of visual angle and in the yellow-blue direction range should not be used to avoid the small-field colorblindness. 7. '''Conventions''': When using color-naming conventions, be cautious of cultural differences. Common conventions are: red =hot, danger, blue=cold, green=life, environmental, go. In China, red =life, good fortune, green =death. === Temporal coding === === Size coding === === Pictograms, maps, images === === Attention/target value === == Conspicuity Guidelines For Mobile Devices == * Use colors with high contrast between the text and the background. Optimal legibility requires black text on a white background, and White text on black background is effective as well. * For text contrast, the International Standards Organization (ISO 9241, part 3) recommends a minimum of 3:1 luminance ratio of text and background. Though a ratio of 10:1 is preferred (Ware, 2000). * When having text on background, purely chromatic differences are not suitable for displaying any kind of fine detail. You must have a considerable luminance contrast in addition to color contrast. * When large areas of color-coding are needed, like with map regions, use colors with low saturation. * Small objects that are color-coded should use high-saturation. * The majority of colorblind people cannot distinguish colors that differ in the red-green direction. * Recommended colors for color-coding: 1. Red, 2. Green, 3. Yellow, 4. Blue, 5. Black, 6. White, 7. Pink, 8. Cyan, 9. Gray, 10. Orange, 11. Brown, 12. Purple (Ware, 2000). |

|

| Line 99: | Line 86: |

| == Readability == In the display of messages we can affect another property of the message– its readability–by the actual choice of words, the sentence structure and the appropriate language(s). |

|

| Line 102: | Line 87: |

| * Communication * Language * Words * Syntax * Reading goals: Skim, scan, search, comprehension, evaluation |

|

| Line 108: | Line 88: |

| == Pleasurability == (branding, compatibility, appropriateness, experience) Good user experience, consistent with the visual character of the surrounding architecture, appropriate ‘style’ to the activity, emotional and aesthetic benefits. |

------- Next: '''[[Composition]]''' ------- = Discuss & Add = Please do not change content above this line, as it's a perfect match with the printed book. Everything else you want to add goes down here. |

| Line 111: | Line 94: |

| * Holistic viewpoint of ‘user’ * Based-on individual users’ interests, experiences, and activities * User relevance and participation * Text vs. subtext |

== Examples == If you want to add examples (and we occasionally do also) add them here. |

| Line 116: | Line 97: |

| '''Comprehension''': Understanding the meaning of a given display so that an associated consequent course of action is both apparent and possible. Comprehension involves recognition as a necessary but not sufficient condition. === User Characteristics === '''Looking and Finding''': Detection and Discrimination. Detection: Determining the presence of an object, target or symbol. Descrimination: Determining that differences exists; discriminating between target objects and non-target objects is determining differences on the basis of which identifications can be made. '''Identifying:''' Identification: Attributing a name or meaning to some object target or signal. Discrimination and identification are often parallel processes, but in psychological terms they make different demands of the presented information. '''Recognizing''': Recognition: Determining whether objects in the display have been seen before. Identification often accompanies recognition. |

== Make a new section == Just like this. If, for example, you want to argue about the differences between, say, Tidwell's Vertical Stack, and our general concept of the List, then add a section to discuss. If we're successful, we'll get to make a new edition and will take all these discussions into account. |

The page is the area that you will spend your time designing for any application or website. A part of it is visible in the viewport of the mobile screen during its current state. There are states and modes and versions to be considered, as well as addressing what is fixed to the page, what can float, and what is locked to the viewport.

The page is the area that you will spend your time designing for any application or website. A part of it is visible in the viewport of the mobile screen during its current state. There are states and modes and versions to be considered, as well as addressing what is fixed to the page, what can float, and what is locked to the viewport.

Based on cultural norms of reading conventions and how people process information, you have to design elements for the page, and place items on it in ways your users will understand. You also want to create information that is easy to access and easy to locate. Your users are not stationary, nor are they focused entirely on the screen. They’re everywhere, and they want information quickly and to be able to manipulate it easily.

Unlike later parts of this book, which cover broader topics, the Page patterns that we will discuss here are contained in only a single chapter:

Chapter 1, Composition

Helpful Knowledge for This Section

Before you dive into the patterns, we will provide you with some extra knowledge in the section introductions. This extra knowledge is in multidisciplinary areas of human factors, engineering, psychology, art, or whatever else we feel is relevant.

For this particular section, we will provide background knowledge for you in the following areas:

- Digital display page layout guidelines

- Page layout guidelines for mobile users

Digital Display Page Layout Principles

The composition of a page has to do with the assembly of components, concepts, content, and other elements to build up the final design. As we already know, consistency is important, so these elements are not placed arbitrarily on the page, or even just as the one page dictates, but on rules across the system, or even the whole OS.

At the highest level is the grid. This is a regularized series of guides, defining the spacing and alignment of the main elements on all the pages in the system, as shown in Figure I-1. Some rules are inviolable, such as margins, and some are specifically designed to offer options for special page layouts, or unexpected future changes.

From these are developed a series of templates, from which each page in the application, site, or other process will be designed and built. This encourages a consistent user and brand experience that supports content organization and layout, advertising require- ments, navigation, and message display characteristics such as legibility and readability.

Patterns within Chapter 1, such as Fixed Menu, Revealable Menu, Notifications, and Titles, are repeated at the same place on each and every page, and so reside in each template. A subsidiary concept is that of the wrapper, which defines these common compo- nents—and others, such as scroll bars—so that they are consistently designed and built for each and every page template.

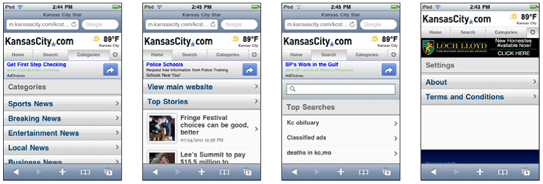

Mobile users have specific tasks and goals. They require that the information be quickly located and effectively organized. Therefore, the page layouts need to reflect the mental models and schemas understood by users. If you ignore these, you will end up with situations such as that shown in Figure I-2. Your users can become frustrated and dissatisfied with their experience, create miscues and errors, and maybe even give up!

Furthermore, using page layouts wisely allows you to organize and place content effec- tively on valuable screen real estate, where every pixel is important.

Page Layout Guidelines for Mobile Users

Here are some page layout guidelines to follow:

- Mobile screen real estate is valuable. Avoid the use of banners, bars, images, and graphics that take up space without any specific use. This use may be secondary, such as communicating the hierarchy or structure, but the designer should always be able to describe the reason.

- Lay out elements within a design hierarchy. There are optional versions, and some interactive types insist that time is another component, but for simplicity the hierarchy is Position → Size → Shape → Contrast → Color → Form. The most important items are larger, higher, brighter, and so on.

Consider the Gestalt laws of Closure, Continuity, Figure and Ground, Proximity, Relative Size, Similarity, and Symmetry. These are discussed further in Part II, Components.

- Use consistent and simple navigation elements. People have limits to the amount of information they can store in their short-term memory. Therefore, they automatically filter information that is important and stands out. Information elements that are excessively displayed and irrelevant will be ignored and overlooked.

- Wayfinding is really rooted in real-world navigation, like getting around town or finding the right room in a building. Kevin Lynch, an environmental psychologist, established five wayfinding elements that people use to identify their position: Paths, Edges, Nodes, Landmarks, and Districts. These same environmental elements are also referenced when navigating digital content on websites or mobile devices. Page numbers, titles, headers and footers, tabs, links, and more provide a lot of help that we’ve inherited almost as a whole for interactive design.

Consider how users will view your page when plotting content. Generally, users will look for high-priority information in the upper left of the content area (Nielsen 2010).

- Multicolumn text is not used to meet some design style, but to restrict line length. And line lengths are not based on fixed sizes, or even percentages of page width, but on character count. Long lines are harder to read. Around 60 to 65 characters (on average) is the maximum length you want to use. A definition for what is too short depends on how many long words you have.

- Titles describe pages, elements within a page, and content sections. Use them consistently and appropriately.

- Default text alignment is left. For right-to-left UI languages, default text alignment is right.

- Try to use bulleted information instead of a table.

The term false bottom, or false top, is specific to interactive design and refers to users thinking they are at the end of the content and not continuing to scroll. If text flows from one column to the next or one page to the next, it must be designed so that the relationship between the columns or pages is clear. “Continued on page 86” is all but a hyperlink from the past, which has been inherited by interactive; “Read the rest of this blog post” is basically the same thing.

Interactive systems have an additional challenge in that the page might be larger than the screen (or viewport, as we often call it).

Getting Started

You now have a general understanding that a page is an area that occupies the viewport of a mobile display. Pages can use a wrapper template to organize information consistently across the OS that will allow for a satisfying user experience. When making design decisions you must consider everything in this page section, even if you don’t have control (i.e., you’re not building an OS). You must know what it might do to your design. Consider your user’s goals and cognitive abilities, page layout guidelines, and the impor- tance of legibility and readability in message displays.

The following chapter will provide specific information on theory and tactics, and will illustrate examples of appropriate design patterns. Always remember to read the antipatterns, to make sure you don’t misuse or overuse a pattern.

Next: Composition

Discuss & Add

Please do not change content above this line, as it's a perfect match with the printed book. Everything else you want to add goes down here.

Examples

If you want to add examples (and we occasionally do also) add them here.

Make a new section

Just like this. If, for example, you want to argue about the differences between, say, Tidwell's Vertical Stack, and our general concept of the List, then add a section to discuss. If we're successful, we'll get to make a new edition and will take all these discussions into account.